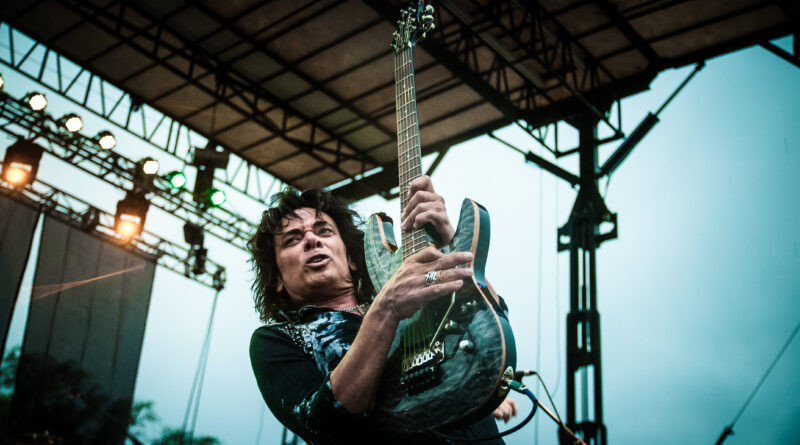

Spinning The Record Straight: A Conversation With Ex-Autograph Guitarist Steve Lynch

Day in, day out, all week long, things go better with rock.

No arguments here. Guitarist Steve Lynch probably wouldn’t either. After all, those are his guitar parts wailing from the eternally-catchy tune, “Turn Up The Radio,” that are heard by millions of people every year, courtesy of his former band, Autograph.

Thirty-six years after it ear-wormed its way into the American hard rock psyche on the band’s debut album “Sign In Please,” the song amazingly still has legs. And probably will for decades more. Funny thing for a band that really wasn’t a band until it landed an opening slot on the tour of one of the biggest bands in the world at the time — Van Halen — without having played a note together onstage.

Autograph ultimately played 48 shows on the tour and began to slowly rise through the hard rock ranks, landing more tours with the likes of Motley Crue and Aerosmith. When it was said and done, they’d recorded three major label albums, played American Bandstand, and were the only band to ever ink a deal with a pen company. Paper Mate, to be exact, who agreed to fund the aforementioned “Turn Up The Radio” video and also provide additional financial support, all because of the album’s title, “Sign In Please.” Funny how things work.

Autograph, consisting of Lynch, frontman/vocalist, songwriter and guitarist Steve Plunkett; bassist Randy Rand, keyboardist Steven Isham and drummer Keni Richards, stuck together until 1989 before disbanding. The band re-emerged in 2014, with original members Lynch and Rand, along with new vocalist/rhythm guitarist Simon Daniels and drummer Marc Wieland. The quartet released a pair of new songs in 2015, followed by an E.P. (2015’s “Louder”) and 2017’s full-length album, “Get Off Your Ass.”

Lynch announced his departure July of 2019, however, leaving the group one last time, citing a need to explore new musical horizons.

It was on one of those horizons that ListenIowa caught up with Lynch to talk about that departure from Autograph, the rigors of the record industry, and more.

ListenIowa: What are you up to these days, Steve?

Steve Lynch: I’m working on autobiography, writing some songs. I have a couple of publishers I’ve been talking to, and I’ve been talking to Leslie Rule, the daughter of Ann Rule, the author who worked with Ted Bundy in Seattle. She wrote the first book about him. Leslie mentioned that if I self-published my book, and hired a marketer, I could make more money with it rather than going with a publisher.

LI: Sort of like today where bands have taken more control of things, whereas back in the 80s, if you signed a deal, the record company would take 90 percent of it and the actual band was left with virtually nothing.

SL: Yeah, we didn’t make any money until after we went gold (500,000 sales). A lot of people don’t realize that you have to sell a boatload of albums before you start seeing any of the mechanical album sales. So, yeah, I’m looking at self-publishing, too. We’ll see. (Laughs)

LI: And the advance you receive on your contract, you have to pay that back. It’s nothing but a loan.

SL: Right. Any of the promotion that the record company does for you, that’s money that you have to pay back. They don’t put out anything out of their own pocket. Everything they spend has to come back to them. You’re not going to make any money unless you sell millions of copies. You look at all the 80s bands now, who were all out there touring before the whole Covid thing broke out, they had to go out and tour because they’re broke. People think they live in a mansion and have all these big classy cars. No, actually the only money they’ve been making for decades is just radio play, and that dwindles down.

LI: Let’s try to set the record straight here: Who tapped the fretboard first, you or Eddie Van Halen?

SL: There was a guy in Seattle named Steve Buffington, who was the first guy who showed me some tapping things, probably back in 1974 or ’75. So I started doing a little bit of it then, and then I saw Harvey Mandel play one time, and he was doing it, so I got into it a little more. But what really set me off is when I saw Emmett Chapman, the inventor of the Chapman Stick, do a clinic during my early days at the Guitar Institute of Technology (GIT) in April 1978. I asked him afterward about what he was talking about when he said he got so far with guitar that he had to come up with an instrument to accompany him better. He said, “Well, can I see your guitar?” So I handed him my guitar and he played two pentatonic scales at the same time, one with each hand. That was great. So I started writing out everything two-handed, and by the end of the year I had enough material for three books. My first book was published in 1979. Eddie was just coming onto the scene at the time and just getting popular.

LI: So if nothing else, you two sort of at least “arrived” at the same time, doing sort of the same thing.

SL: I’m like eight days older than him, so I figure that we were at least listening to the same people. The last person who I listened to who really influenced me was Allan Holdsworth. Through the years, I’d been influenced by Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, David Gilmour, Al DiMeola, but Holdswoth was the last one I was influenced by, and that was in 1978, because I didn’t want to sound like anybody. I’ve got one of those brains where anything I hear, it sort of stays in my head and I start playing like that, or I start writing like that. So I stopped listening to any guitar players in 1978.

LI: Recently, you said in an interview that prior to Autograph’s opening show on Van Halen’s 1984 tour, you were given an edict in which you were told you couldn’t do the tapping thing.

Yeah, when we went out on tour from them, I got word. I’m not certain where it came from, but I know that Eddie had heard about me, because I’d written books about it, and I was pretty well known in the L.A. area before Autograph for that tapping technique, and was getting a lot of studio work because of it. I think that when he found out we were on tour with them, the next thing I know, their tour manager is coming up to me and saying I can’t do it (tapping) on the tour. I was like, “What?”

LI: How did you deal with that?

SL: I had to go up there and improvise the solos, but eventually I just said, “To hell with it. If they’re going to fire us, they’re going to fire us.” I just started doing it anyway.

LI: How did guys land that opening slot with Van Halen when you weren’t even an actual band yet?

SL: We weren’t. We were just guys who got together at Victory Rehearsal Studios and had played in different incarnations of bands. We’d get together on the weekends to just jam out, drink beer, have fun and play AC/DC and Thin Lizzy songs. (Laughs) We started writing some original stuff and Andy Johns, a producer, came down and loved our original songs. He wanted us to cut a five-song demo. He had free time at a studio. We thought that was great because didn’t have any money. (Laughs) We recorded it, and it came out really good. At the same time, our drummer, Keni, was jogging buddies with David Lee Roth. David asked him one day what he was doing, and Keni told him he was playing with a band called The Coup on A&M Records, but that he had just cut this other demo with some other guys who just get together and have fun. He played it for David, and David loved it and asked if we wanted to go out on the 1984 tour with them. Me and the keyboard player were playing with Holly Penfield on Dreamland Records, Steve Plunkett was playing in a band called Silver Condor on Columbia Records, and Randy Rand was playing with Lita Ford. We’d done all the recording with the bands we were in and thought we might be able to get away for a few months. So, we did. We told them we’d go out on tour as long as we can until our other bands need us. When we went out, it was such a success, that we decided to quit our other bands. (Laughs)

LI: And I understand that you didn’t even have a band name when you accepted the slot.

SL: We actually thought of the name Autograph on the way to the first gig, which was in Jacksonville, Florida. We drove all the way there from L.A., straight across on Interstate 10 in this old broken down Winnebago. We came up with the name in Texas, and thought, “That’s something we can use temporarily. Nobody else is doing it, so let’s go with that.”

LI: And then one thing led to another and the next thing you know you’re rubbing elbows with Dick Clark on “American Bandstand.”

SL: Here we are on tour, and we didn’t expect to be getting offers from all these record companies like Geffen and Warner Bros. and Epic. But RCA offered us the best deal with 100 percent of the publishing. We basically did the deal backstage at Madison Square Garden. All of a sudden we were on “American Bandstand” twice, and “Solid Gold.” I never thought in a million years I’d be on “American Bandstand.” But there I was, talking to Dick Clark. (Laughs) That was quite the adventure.

LI: Autograph landed some prime opening slots on tours during this time, from Motley Crue to Aerosmith to KISS. Anything particularly memorable stand out from those tours?

SL: We had 30 minutes with Van Halen, but I think we had about 50 with Motley Crue. We were selling a lot of albums at that time, so weren’t just a half hour warm-up band by then. We were helping sell out auditoriums with Motley Crue and Aerosmith. We were helping sell a lot of tickets, and that’s why they wanted us on tour.

LI: The Motley tour must have been interesting.

SL: Oh boy. (Laughs) That was over the top. I remember one time me and Tommy Lee (Motley Crue drummer) go so drunk on Jack Daniels one night. The next day he said to me, “Aw man, I don’t know how I’m going to play tonight. I’m so baked.” I asked him how he was going to do his drum solo upside-down, but he did. I was standing at the side of the stage watching the drum riser go up and turn over. He was upside-down and playing when he paused for a second and just kind of threw up all over the audience. That had to be brutal. The audience thought it was part of the show until they realized it was puke. (Laughs) They were flipping him off and everything. It was hilarious. But after that tour, I quit drinking for five years. (Laughs)

LI: What do you think was Autograph’s peak, musically?

SL: The debut album, there was a lot of energy, it was exciting, we were in there with Neil Kernon, who is a great producer. But as far as my favorite album, the one with the best production and writing, it was the third album, “Loud and Clear.” We were really seasoned songwriters before Autograph because we’d been in so many original bands, but we were really so by the time that album came out.

LI: What was one thing about Autograph that people didn’t know that you wish they would have?

SL: People kind of looked at us like a one-hit wonder, but actually there are other songs other than “Turn Up the Radio” that did better in other countries. Like “All I’m Gonna Take” from the first album, and “Blondes in Black Cars.” A couple of our ballads did really well. One of the things that happened to us was that Bob Summers, the president of RCA at the time, died of AIDS. Bob Buziak came and took his place, and in the New York offices, they replaced 50 percent of their staff with all these young yuppies who had no idea how to market music. We suffered greatly for it. So did the Pointer Sisters, Kenny Rogers, The Eurythmics and Mister Mister. We all suffered from it. Everybody had albums coming out at the time, and they didn’t put any promotion behind it. I think that our third album would have done really, really well if we would have had some promotion behind it.

LI: But it didn’t, which led to Autograph splitting for good in 1989.

SL: “Loud and Clear” came out in 1987 and we kept on touring. We were actually doing demos (which ended up appearing on the 1997 release, “Missing Pieces”) for the next album, because our deal was up with RCA and Epic wanted to sign us. And then the grunge thing came in. Overnight, it just wiped out the whole 80s thing. It was gone. Record companies wouldn’t have anything to do with any 80s bands anymore. It was like, “Your career is over.” I’m originally a Seattle guy, and to have that music come out of there, I’m going, “These were the garage bands. How are they becoming huge?” But I think the industry was looking for something a bit more raw and spoke directly to the younger audience. Right at the end of the 80s, it got a little too homogenized. And that’s because of the record companies. They wanted bands to be like Def Leppard and have four or five hits on each album. There was overproduction on everything, but that’s not what rock ’n roll is about. But they didn’t care about those things. All they cared about was sales. It became very stringent on the artists.

LI: There was a big gap with no Autograph at all, then in 2014 you guys decided to give it another try, this time, though, without your original vocalist, Steve Plunkett, who decided not to participate. Did you talk to him at all and try to convince him otherwise?

SL: We asked him first, but he said he was really busy with the TV and movie stuff, which we was, and making good money at it, too. He also said his voice just wouldn’t do it anymore. Toward the end of Autograph, he was starting to have problems with it. He mentioned that he had sang a couple of years previous with a band that just wanted him to get up on stage and sing a couple of Autograph songs. His voice just gave out, he said. And that was just with a couple of songs. So he said there was no way he could do it. That just happens with some singers. Their voice gives out, and there’s nothing you can do.

LI: But you guys decided to move forward, cut some new tracks, released a couple of albums, etc. The songs were played tuned down, though, which gave the older songs a totally different feel. Looking back, was that the right move?

SL: Yeah, we tuned things down a whole step. It was a heavier sound, plus it’s easier to sing to. For me, the background vocals were much easier to sing, but, I would have preferred to have kept it maybe down a half step. And I really missed the keyboards. In the beginning, I thought it would be good without the keyboards, but I did miss them. They were an integral part of the original Autograph sound.

LI: You stuck with this incarnation of the band for a few years before deciding to leave. What went into making that decision?

SL: I stuck with this one almost as long as I did the original Autograph. I just didn’t see a future with the whole 80s touring thing anymore. Obviously it tapered off with the pandemic, but I saw like, in one year, five promoters went out of business who were doing the 80s thing. Then the 90s thing was starting to come in. The 80s audience was starting to dissipate. I saw that with the festivals and other things that, no matter what bands we were playing with, the attendance was just not there anymore. But the main reason I quit is because I just felt like, you know, I’m getting older, and I want to do something completely different. Just like I did with my solo album, Network 23, which was completely different from the original Autograph. I wanted to do something that people don’t expect from me. So on my new project, Blue Neptune, that’s going to have some orchestral parts in it. I want to incorporate strings, saxophone, different African beats. I want to incorporate all kinds of funky stuff and really mix it up. I want to play the songs that I want to play. When we were writing songs for [the latest Autograph album] “Get Off Your Ass,” I didn’t even really even present them to the band, because I knew it just wasn’t right for it. I felt that way with the original Autograph. I had to kind of force myself to write in that genre. The same thing was happening now, so I decided it was time to bow out and put all my efforts into a solo album.

LI: So what’s on your docket of things to do now?

SL: I’m finishing up my book. After the marketing, which will probably be until March, I’ll start in on the Blue Neptune stuff, which I’ve got most of it written. It’s just a matter of sitting down and starting to record it now. I’ve learned in my older years that you do one thing at a time. (Laughs)

LI: Otherwise they all suffer.

SL: That’s exactly right. I’ve learned to focus on one thing at a time, do the best job I possibly can on it, and then move on to the next thing.