Heavy Duty: A Conversation With Ex-Judas Priest Guitarist K.K. Downing

After 42 years as one-half of the iconic twin-guitar sound that helped catapult legendary heavy metal band Judas Priest from its dark, industrious beginnings in Birmingham, England to some of the largest stages in the world, K.K. Downing is finally ready to talk.

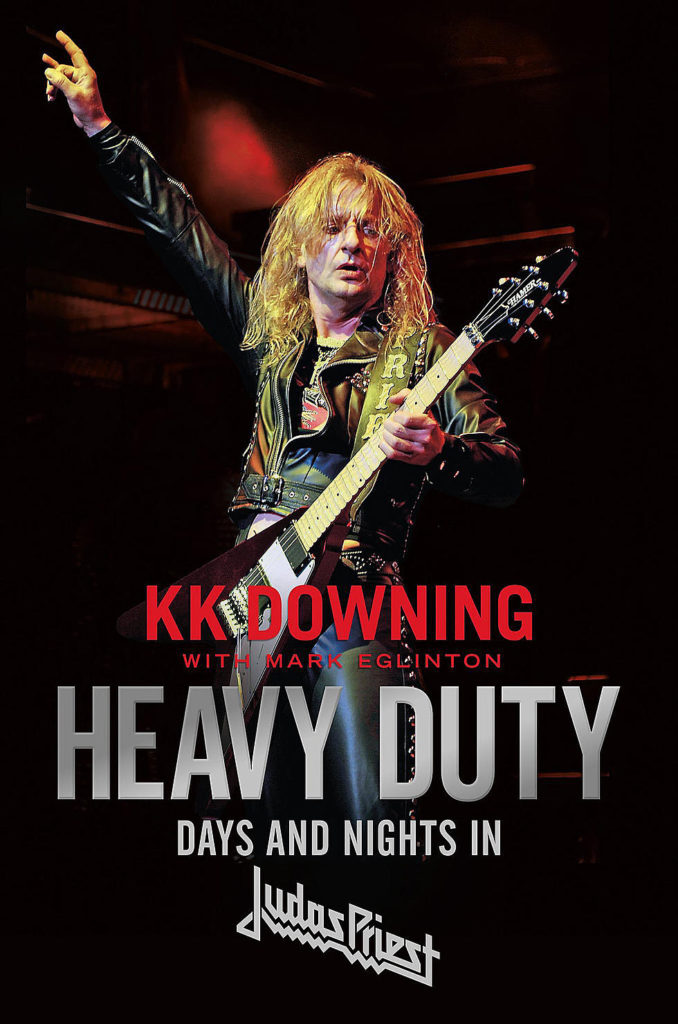

Having been a primary cog in the Priest metal juggernaut for more than four decades before leaving the band in 2011, Downing has amassed a treasure trove of stories and experiences that he recently unveiled to the world with the release of his new autobiography, “Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest,” released on Sept. 18 by Da Capo Press.

Downing sat down with writer Mark Eglinton to take readers on a chronological journey of his life that begins with a despair-filled childhood, thanks to a paranoid, gambling, and abusive father who Downing struggles to find a good word for. After escaping the horrid confines by quitting school, leaving home and landing a job at the age of 15, the young Downing hit a pivotal moment with the discovery of a young and upcoming guitarist by the name of Jimi Hendrix, where Downing’s rock god guitar seeds were sown.

“Heavy Duty” is an entertaining and introspective look at Downing’s career from his pilot’s seat inside one of heavy metal’s most influential bands. Woven amongst the pages are the tried and true rock n’ roll sordid revelries of excess and sexual escapades, sure, but not in the proverbial “notches on a bedpost” sense. It was what it was — the glorious 1980s, where living large was expected, not shunned. Downing also takes time to discuss his on-again, off-again working relationship with fellow guitarist Glenn Tipton, and the frustration of not being able to ride Judas Priest’s most successful commercial album, the groundbreaking “Turbo” in 1986, to the land of megastardom.

But Downing’s look back isn’t exclusively regret or misgivings. At the end of the day, he said, Judas Priest will not only be remembered in music history as one of the forefathers of heavy metal, but as innovators as well.

“You can ask a lot of people in the world to name a heavy metal band, and an awful lot of them would start with Judas Priest,” he said. “For me, metal could be about a lot of different things. We pushed the boundaries in every which way, and we felt we need to do that to get people on board. We knew that there were a lot of people who loved what we were doing, but we still felt like we needed to widen the spectrum to get noticed.”

ListenIowa recently caught up with Downing to talk about the book, his life and his thoughts on the current version of Judas Priest.

How has the experience of being in the spotlight for the release of an autobiography instead an album been?

It’s something different. They say a change is as good as a rest. This is kind of interesting. I’m really, really pleased with the success so far. It’s a bit different from releasing an LP, though (laughs).

Your dad, with his phobias, gambling habits, and just his overall treatment of the family, made it tough for you in your growing up years. Was it difficult to revisit those early years?

It kind of was. Most of us, when we look back, we like to remember the good things and kind of shun off the not-so-good things. The war finished in 1945 in the U.K., and my parents had my sister, Margaret, in 1949. It was before contraception, and it was a mistake, you know? My mom kind of wanted it, but my dad didn’t. Millions and millions of people, I’m sure, suffered the same thing with the unwanted, kind of shotgun wedding. I got out of there at the age of 15 and did myself a good favor. It was never going to get any better.

That was when you dropped out of school and got your first taste of life, so to speak. Your eyes were opened to something different than what you’d known in your house. That was a real crossroads moment.

It was. I was prepared to sweep streets, clean toilets, or do anything. I just wanted my freedom. I just wanted to break through from the penance I was serving. Fortunately, I found a job in a hotel, and they gave me a little room. I had wings and freedom, and there was normality around me — normal people. That gave me a new lease on life. And like so many people my age, we started to find music around that time. We had pop music, with Elvis, the Beach Boys, The Beatles, etc., but we also had the blues movement coming through England right around that time in 1965 with Paramount, so a lot of the bands we were listening to were influenced by that music, whether it was Led Zeppelin, Free, Jethro Tull, Queen, etc. It was all kicking off, and I got on board.

Speaking of crossroads, soon after that you discovered Jimi Hendrix, who became somewhat of a beacon of light for you. You travelled extensively as a boy to see him play.

Hendrix pushed the boundaries, and I could hear some things in some of his music that we now term as “heavy metal” in this day and age, and so that seed was sown in me. There are a few other tracks from the early Stones, or early Kinks, but only little bits and pieces. It infused itself in me, and I wanted more and more of it.

You went as far as stealing a guitar pedal from Noel Redding at a Fat Mattress gig because he was in Hendrix’s band, and you thought Hendrix might have played through it.

Yeah, and he definitely stole that from Jimi for sure because it was one of those Dallas Fuzz Faces, which are very rare now. I don’t know what happened to mine.

You also mentioned just popping your head into Hendrix’s tour bus window on a whim, and he eventually gave you a Coca-Cola bottle, which ended up being about three weeks before his death. That would be quite the collector’s item.

No, I don’t know what happened to it. A lot of things were going on in my life then. I was actually getting fired from my job and had to go back home, regrettably, for a few months. I took up some up small jobs, found a tiny space on my own, and was working on playing guitar. But as soon as I got the equipment that I wanted — a nice Gibson SG and a Marshall stack — that was it, really. I stopped working and began playing in bands and whatever I needed to do to survive. I knew it was a risk.

And this is when your love of the harder, darker side of music blossomed, too.

I would hear a song by Deep Purple that kicked the boxes. Songs like “Child In Time.” That was heavy metal to me. It had some of the ingredients. I took this with me throughout my life and my career, and it was what I was trying to create. So much so, that even when Black Sabbath came on board, we were playing gigs as a four-piece Judas Priest. Eventually it evolved from blues, to progressive blues, to rock to heavy rock, and then heavy metal. The rest is history. I was part of that evolution, and I’m very proud of that. I couldn’t have done it alone, and I’m very grateful to my band mates.

Much has been discussed about your relationship with Glenn Tipton. You mention it being a sort of “my way or the highway” feeling with him at times, and a bit of distrust grew out of it.

Glenn came from a normal, respectable home and went to grammar school and that was probably the difference, really. I was dragged through school (laughs). I didn’t make the grades, and it was a rough start in life. We still had our musical minds together, though. We had a good partnership and a great friendship of a certain type. But I kind of had this heaviness in me, these dark things that I would bring to the table. Glenn’s stuff was a bit more melodic. That’s kind of the way it was. In those days, rich kids, they liked pop music, and it was a happy world. There were intermediate families that were a bit of a mix. I fancied something that was for the working class, and that became infused with what blues music brought, and that became progressive blues and rock blues. It was a magnificent evolution, a complete roller coaster.

Will we ever see an evolution like that, and decades like the 70s and 80s again?

Probably not. We are pretty much dinosaurs. You can’t you keep re-inventing the wheel, can you? We’re pretty much a dying breed who came, made our mark, and it’s etched in stone. It will always be there.

You were particularly miffed at Iron Maiden in the early days for what you perceived as their arrogance, especially since they weren’t as established as Priest and were opening shows for you.

For me, to get to where I was at that time in 1980, it was a hard, hard climb. I was working casual labor trying to make ends meet. I somehow got the feeling with regard to the Maiden boys that it all went a bit too easy for them. They got a record deal pretty quick. Our first two records, we didn’t make any money from them. It was a long, hard penance, but I think it made us better people for it. So when you get the young bands coming aboard with a bit of arrogance, and they’re saying things in the papers, I began thinking, “Whoa!” And with Maiden, I never got how all the best song and album titles, a lot of them were all from books or movies, right?

You may be on to something there, yes.

So with Priest, we would dig hard and deep into our souls for great song and album titles. I didn’t realize that it could be that easy. (laughs) A lot of these good book and movie writers, they put a lot of hard work into coming up with these great titles. The bands that just kind of cherry-picked them, I never quite got. But I’ve got total respect for the guys in Maiden. All of those things that happened (between the two bands), they grew out of that, and they’ve become a great band. A lot of water has gone under the bridge since those days.

In the book, you discuss former Judas Priest drummer Dave Holland, who left the band in 1989 and afterward basically became a ghost with regard to even being mentioned. (Editor’s note: Holland was found guilty of attempted rape and assault of a 17-year-old male with learning disabilities in 2004. He died in early 2018)

When Dave left, we just carried on. The machinery has to keep going. You kind of go forward in any way you can and keep yourself busy. I don’t know what Dave went on to do, but he got himself into a mess. I’ve been in enough situations and courtrooms in my life that I’ve seen a lot of things happen. I’m not a person who pre-judges anybody. A lot of innocent people have been hung, and a lot of guilty people have gone free. Mistakes do get made, but I wasn’t there, so I can’t pre-judge. Dave was the person who I knew him as, and I’m sure the fans feel the same. Dave was an integral part of Judas Priest for all the years he was in the band. He was a good bloke to me — always a good guy. And I will always remember him as that.

It had to be incredibly difficult to leave Priest in 2011, something you’d worked so hard to build and create.

It was the hardest thing I had to do in my life, and I always thought that I was a very strong and resilient person. But I know now that it doesn’t matter how strong you are, there are going to be battles you have to fight in life. And everybody has a breaking point.

What brought things to a breaking point, then?

It just wasn’t the band that I’d had for so long, that had so much determination and 110 percent spirit and was going out there every night and giving everything. That’s what you have to do. There was a good feeling about having to do that every night. There were nights when I’d see Rob (Halford) tip his boots upside down backstage after a show, and water and sweat were pouring out of each one. These were the good feelings — the battle wounds. I would look across at my band mates, and they would be absolutely exhausted. This was the standard that I always expected. But that just seemed to drop off. It seemed that we were a bit complacent and kind of going through the motions, not so much that the audience noticed, but I did on stage. Glenn drank beers before and during a performance, and it made me feel nervous. I wasn’t getting the enjoyment from the music in the way that I should have. I knew I wasn’t there to come down or criticize people, though. Some people go onstage with a joint or a bottle of Jack Daniels, and they do it their way, which is rock n’ roll; it’s not for me to criticize, so if it’s not going to change, I’m going to have to step down, because it’s just not what I wanted. A lot of things were being thrown onto the camel’s back, but being asked to do an EP after “Nostradamus?” Come on. Judas Priest is not an EP band. I was thinking of a lot things at that point, and that just pushed me over the edge.

Would you even entertain the thought of playing live with the current version of Priest, or maybe go into a studio to record a new song? Anything?

My main thing is that, when I step on that stage, everybody has to give 100 percent. The music has to be absolutely, 100 percent hot, and it has to be done with as much absolute precision as it can. We all make mistakes, but that’s why we all have to be 100 percent coherent and absolutely in tune with each other. The stage can be a dangerous place for a lot of reasons — equipment dropping from the sky, some psycho idiot jumps onstage and you saw what happened to my good friend from Pantera (Dimebag Darrell, who was killed in 2004 while performing). You have to be very aware of everything and cover for your band mates. If someone makes a mistake, everyone has to be on board and help cover for the guy and keep the show going. All those eyes and ears are on us, and we’d have to be the Judas Priest that the people have paid and travelled for. That’s all I ask. I know Richie (Faulkner, who was hired to replace Downing) is a good player and plays very, very tight, and the other guys do as well. If I come back, it would have to be a partnership, and I’m sure all the other guys would be on board as well. So…. maybe. We’ll have to see what happens. Total respect for them, though. We went on a journey together, achieved a lot of things, lived a life together, and I’ll be eternally grateful for their part in helping to achieve that.

Pingback: K.K. DOWNING Says DAVE HOLLAND Was 'A Good Guy' And 'An Integral Part' Of JUDAS PRIEST - Empire ExtremeEmpire Extreme

Pingback: K.K. DOWNING Says DAVE HOLLAND Was 'A Good Guy' And 'An Integral Part' Of JUDAS PRIEST - Krister Lindholm Experience

Pingback: K.K. DOWNING Says DAVE HOLLAND Was 'A Good Guy' And 'An Integral Part' Of JUDAS PRIEST – 695TheRock.com

Pingback: K.K. Downing Says Dave Holland Was 'A Good Guy' And 'An Integral Part' Of Judas Priest - Blabbermouth.net