What Could Have Been: A Conversation With Connie Valens, Sister Of The Late Ritchie Valens

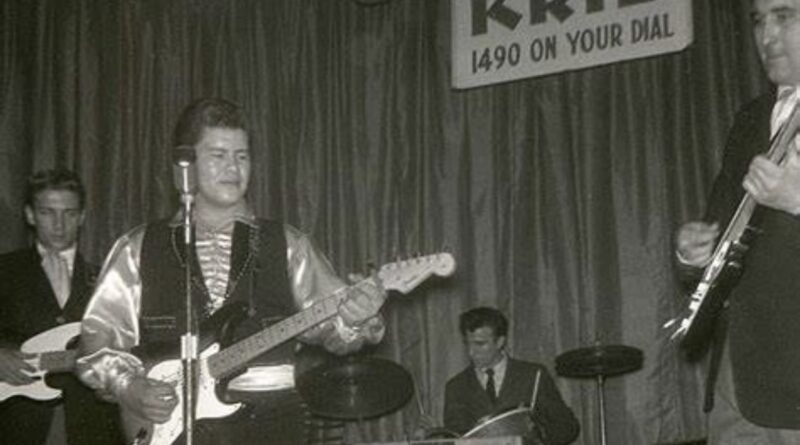

At 12:55 a.m. on Feb. 3, 1959, a handsome, young 17-year-old budding rock n’ roller named Ritchie Valens — along with fellow musicians Buddy Holly and J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and pilot Roger Peterson — became indelible parts of American music history.

Sadly, their entries onto those hallowed pages came with a heavy price. The heaviest of all, as a matter of a fact — their lives.

After a Feb. 2 performance at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, the foursome boarded a small plane just before midnight, one that Holly, himself, had chartered. As fate would have it, it would be their final moments on this Earth.

The plane crashed just a few minutes after takeoff, coming to rest in a frozen farm field a few short miles outside of Clear Lake. In an instant, the very landscape of music had been altered. What could have been, would never be.

It was “The Day the Music Died.”

Over the years, many stories have emerged of the fateful night, and a one, Connie Valens, has likely heard most of them. But her perspective of that night, and more, is different than most. She, being the younger sister of Ritchie Valens, has had to live it in real time.

Valens, who currently resides in northwest Iowa, sat down with ListenIowa to give an inner perspective as to what it truly was like before — and after — that fateful night in Clear Lake.

ListenIowa: When did Ritchie begin getting attention as an artist?

Connie Valens: He was discovered, and all of a sudden, just like that, he wasn’t home much anymore. When he did come home, I remember him being in his room with the door closed, and when the door was closed, we couldn’t disturb him. That’s when he would be writing. Bob Keane (Valens’ producer/manager) had sent home a reel-to-reel recorder with him, and we would hear him in there playing guitar, writing, singing and recording. He would take those recordings to Bob and see if there was anything there they could use. They developed “Donna,” “Come On Let’s Go,” and others from those recordings I’m sure.

LI: So although things were somewhat normal, there was a sense that something big was happening there?

CV: There was something going on. He was special. As an 8-year-old, I can remember standing outside the door with my ear to it, and hearing the guitar and stuff. We didn’t dare say a word because we didn’t want to interrupt him, but let’s just say we were wondering what was going to come of this and what was going to happen to us.

LI: Certainly. It’s hard to have much perspective on life and what is truly happening when you’re 8, so it had to be somewhat confusing as well.

CV: Yes. I think I was more worried about him going away. He was home less and less. Mom would say, “Ritchie’s going to be gone, so let him rest,” or “Ritchie’s home now, let him rest.” We missed him. I adored him. Literally. He was more than a brother. He was our babysitter when we were growing up; he took care of us.

LI: It didn’t take long before he was really making a name for himself. What was it like from your perspective, suddenly being the sibling of a “star”?

CV: We loved it, but we loved him, obviously. He meant everything to us. My sister and I used to take Ritchie’s publicity pictures and either mom, or sometimes Ritchie, would sign them, and we would take them and sell them at school for five cents each. It was a great time.

LI: Do you remember the last conversation you had with Ritchie?

CV: Ritchie was popping in and out by that time, but I can remember him coming home from New York. They were going to pick him up at the airport, and it was pretty late. At our home there was a little space between a window and an alcove with a short little wall. There was a chair there. I had grabbed one of the kitchen chairs and put it right there, because our house was so crowded, and everyone was there waiting for him. I sat there. And sat. And sat. And sat. I remember almost falling asleep in that chair. My mom told me to go to bed, but I said, “No, I’m not going to until he comes home.” All of a sudden there’s this commotion, and the door opened, and I could hear him laughing and walking up. I was supposed to be the first one, but all these people got in front of me, and because I was pretty short, got pushed back, almost to my chair. He finally looked down and saw me standing there and said, “Mi ha,” which means, “my daughter,” and he picked me up. I went to kiss him on the cheek, and he laid one on my lips! He was laughing. He put me down, and I wiped it off and said, “Ritchie!” He laughed, and I thought, “Is that what I waited up for?” and went to bed. That was my last real, real memory of him.

LI: How did you learn about the accident that took his life in Clear Lake?

CV: We actually didn’t know anything that night. I didn’t know about it until after school the next day. My sister and I were walking home from school, and somebody came up to us and goes, “You’re Ritchie’s sisters.” And we said, “Uh-huh.” And he goes, “Well, he’s dead.” Talk about your heart falling to your knees. We said he was lying and that he was just jealous. My sister and I looked at each other and started running home. Whoever was supposed to pick us up did so about halfway there, but when we got home, when we jumped out of the car and ran into the house, we noticed all these people there. We wondered why they were all on our lawn.

LI: You had feeling something was wrong, though.

CV: Yes, I looked at mom, and she looked at me, and I knew something was very wrong. She was sitting in a chair in the middle of the living room with all these people around her, and she said, “Perdimos a tu hermano,” which means, “We lost your brother.” I remember dropping to my knees with my head on her lap, and she put her hand on my head as I was sobbing.

LI: That had to have been extraordinarily difficult for someone your age.

CV: I was a huge Shirley Temple fan, like most kids my age, and there was a movie called “The Little Princess,” where the father of a young girl was lost at war, but she knows he isn’t dead. It turned out the father wasn’t dead but had amnesia from an injury he suffered. Well, in my mind, Iowa was this cold, dark place, too, that had taken my brother during the night. But I thought a farmer had found him, and neither he (Ritchie), nor anyone else, knew who he was. He was still alive. My brother would come back. That’s what I told myself. But then when people would talk about Ritchie, or I would hear his music or see a photo of him, it kind of stole my secret; it made it not true. And so, so hard.

LI: Years later came the major motion picture, “La Bamba,” starring Lou Diamond Phillips as your brother. Was that a difficult time for you personally as well to rip that Band-Aid off once again?

CV: Up until then nobody knew Ritchie was my brother because his death affected me so deeply and immensely that I just really never got over it. Here I was, an 8-year-old, and all of a sudden my brother is gone. My mother suffered a nervous breakdown less than six months later. We were pretty much on our own, left to survive with the family that was remaining. I just never talked about it. I just couldn’t. I didn’t talk about him. Nobody at work knew he was my brother. I didn’t have a picture of my brother in my home, or a CD, an album, nothing. I can remember sitting in a car with one of my friends and one of Ritchie’s songs came on and I started crying. They were stunned and didn’t know why I was crying. There was just no closure, and I don’t know if I’ll ever have total closure. He’s so much a part of our lives every day. There’s not one day that I don’t think about him. Because of “LaBamba,” though, I was able to let go of all the deep pain and sadness I had carried all those years. Lou literally became Ritchie for those three months on that set, and he helped us all with the closure. It was very healing for our family, and helped me to say goodbye.

LI: So making that movie actually did the opposite — it helped you.

CV: They were filming in Pacoima (California) one night, and they had made the airport look like the one in Mason City, and Lou was standing by the plane. Something within me rose up, and the next thing I’m doing is walking across the tarmac to where he was standing where they were filming. And he’s standing there, looking sick, like he’s supposed to, and at that moment, he was Ritchie. And I started crying. I looked in his eyes and asked, “Ritchie. Why? Why did you get on the plane? Momma told you not to get on little planes. Why did you go, Ritchie?” Lou just put his arms around me and told me he was sorry. Taylor (Hackford, the film’s producer) got really upset with me and said, “You can’t do this. We’re filming.” But Lou was like, “Leave her alone. Just leave her alone.” They walked me off the set, and that was my final goodbye.

LI: Stories always emerge after these kind of things happen. What have you learned about Ritchie over the years that you never knew?

CV: There’s a guy named Robin Luke, who was performing at the Surf four years ago. He had performed with Ritchie. We met him and he told this story about how he had gone back to the theater one night because he left something backstage. But once he got there he found Ritchie there with a sleeping bag. He said, “Ritchie, what are you doing? You know they have room for the artists. And Ritchie looked at him and said, “They told me that if I stayed here and don’t use a room, they’ll give me an extra $40 a night. I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be able to do this, but I really want to make money for my family.” I just wanted to drop down to my knees and cry. It just told me that Ritchie didn’t know how good he was. He was too young. He was 17. He was just doing what he could do for his momma and his family. I also met Dick Clark in the early 1990s. The Postal Service was dedicating the new rythym and blues series of stamps with Buddy Holly, Ritchie, Elvis Presley, Otis Redding, Bill Haley, and others who were being honored in the collection. I was invited on behalf of our family for the unveiling. I asked Dick if there was something he could share with me about something Ritchie did, or said, to him, and he said, “I can tell you this: He was humble, polite, kind and a great kid who didn’t even know how good he was.” LI